© 2018 Inger Lise TEIG

2018 — №2(16)

Keywords: Organizational ethnography, lack of resistance, category struggles, deep management

Keywords: Organizational ethnography, lack of resistance, category struggles, deep management

Abstract: This article builds on ethnography of the ‘patient flow’ system at a Norwegian public psychiatric hospital. The emphasis on patient flow in the psychiatric hospital represents a shift to a more process-based form of patient administration and organizing, revealed in the vocabulary, technology and practices of local managers and clinicians. The article examines how the metaphor of ‘patient flow’ produces and naturalizes a certain type of structural dynamics of power through its categories and its structural process. Within organizational institutionalism and in the sociology of professions clashes between managers and professionals have often been studied as a conflict between institutional logics or between professionalism and managerialism. This article argues that the procedural logics that is introduced in this hospital, and in general in Norwegian healthcare, conceals such tensions, as it is difficult for professionals to refuse flow as the dominant terminology. The organizational processes involved appear for health workers as necessary and inevitable preconditions for an adequate organization of psychiatric health care.

‘We have a huge challenge to constantly focus on;

namely making patients flow through the system’.

(senior manager, psychiatrist)

Introduction

The increased application process-based patient administration in psychiatric health care in Norway is focusing on improving the patient journey through increased access and reduced waiting time and is conceptualized by the category ‘patient flow’. The category ‘patient flow’ is at the center of attention in this article. I analyze how the category and technique of patient flow unfolds in a Norwegian public psychiatric hospital as the overall procedural logic through which the senior managers seek to produce organizational efficiency. I do not focus on the category ‘patient flow’ per se but seek to specify the ‘discursive and practical operations through which the category becomes attached to the events it purports to describe’ (Power 2007: 4). The main interest is to explore the practices of managing patient movement and how the category ‘patient flow’, when operationalized into specific categories or practices by senior managers and clinicians, is entangled in discourses of efficiency and productivity that are intrinsic to process-based principles of administration.

Processing patients is a key activity in healthcare systems, and in order to do that a system has to be in place to define, measure, control and improve processes with the goal to meet customer and health authority requirements (cf. McNulty and Ferlie 2004). The patient flow technology I observed in a psychiatric health hospital in Norway works to reconfigure organizational practices and processes parallel to what Radnor et al. describe for the implementation of Lean in the English NHS (Radnor, Holweg and Waring 2012). Organizing the hospital around the logic of processes as opposed to functions implies an increased focus on organizational structures and new practices for the actors involved. It has been suggested that the ‘logic’ of managerialism has come to replace the ‘logic’ of professionalism in the social organization of healthcare (cf. Waring and Bishop 2010, from Kitchener 2000). Health professionals have long been described as being in conflict with the new ‘managerial spirit’ in health care (see Brown & Crawford 2003), and clashes between managers and professionals are well documented (see for example Exworthy and Halford 1999; Freidson 2001; Dent 2003; Kirkpatrick et al. 2011; Radnor and Osborne 2013). Fournier (1999) proposes that clashes between managers and professionals have dissolved because professionals have increasingly been exposed to a ‘responsibilization’ process and have become ‘re-professionalized’ as medical managers (see also Grey 1997). There is thus a trend towards enlisting professionals into managerial tasks with responsibility for the whole system, and one may thus also here speak of a certain degree of managerialization (Harrison and Pollitt 1994; Fournier 1999; Fitzgerald and Ferlie 2000).

In this article, I argue that managerial and professional tasks overlap, and that the potential conflicts do not seem to be present to the extent predicted by traditional perspectives. Patient flow as a procedural logic contributes to conceal rather than promote tensions between managers and professionals, as it is difficult for professionals not to accept that flow is a necessary precondition for the current organization of healthcare. The patient flow becomes operative through two effects: a) the category ‘flow’ itself influences or even constitutes perceptions of reality; the language categories used have an ideological function, and b) the practice of flow establishes and reinforces the dominant production system of the psychiatric hospital and actually prevents the raising of clinical considerations. Our work is thus attentive to local experiences patient administration processes and it explores how these processes are accepted and partly opposed in an on-going process of organizational change.

Sources of data

The article builds on organizational ethnography the author conducted from 2006 to 2008 at a large public psychiatric hospital (an autonomous division of the regional Health Enterprise). The specific hospital had then recently been merged with several university psychiatric clinics and local district psychiatric centers (the DPCs) with the managerial intention of becoming a more “efficient” and “patient-oriented” psychiatric hospital. The material is based on ethnographic material gathered through observation of daily clinical and managerial work and 32 semi-structured interviews. The ethnographer participated in senior management meetings, clinical meetings, seminars, courses, daily events and talked with clinical staff (psychiatrists, nurses and other health professionals), administrators and managers throughout 16 months, two to three days a week. Notes were made at all events, meetings and seminars. Field techniques were semi-structured interviews, observations and analyses of internal documents. Selection, data collection and analysis were carried out in accordance with a ‘situational analysis’ (cf. Evens and Handelman 2005, 2006) approach that put weight on the event (the situation). The ethnographic ‘extended-case’ or ‘situational analysis’ was developed by the British anthropologist Max Gluckman at the Manchester School of Social Anthropology. Gluckman proposed to trace the relationship between the general and analytical statements through the dynamic particularity of the case, and argued that by taking the actors and their roles in any particular incident and to trace these actors through other incidents, one could link the varied incidents to one another and identify the mechanisms operating in the relevant social order (Evens and Handelman 2006). This ethnographic method emphasizes that the event or situation is never merely illustrative or a gimmick (Kapferer 2005) of a theory, but has its own particularity that operates in a social order that integrates macro dynamics into its micro practices. Building upon this method, the data generation was performed by studying actors and their roles in a particular incident and then tracing these actors through other incidents; in this way, I could link the varied incidents to one another in order to identify the structural contradictions and the resolving mechanisms in the social order. By scrutinizing particular situations, especially conflicts, as complexes of connected incidents that occur in the field identified the mechanisms underlying the development of the situation (“the event”). The event brings its elements together in a unique way that potentially contains transformative possibilities. In order to achieve any form for ethnographic explanation and understanding of an event (cf. Evens and Handelman 2005, 2006; Kapferer 2005), we must attend to the understanding that micro dynamics are integral within larger processes. The analysis of sequences of events over quite a long period where the same actors were involved in a series of different situations enabled me to trace how events chain on to others and how they were linked to one another over time (cf. Mitchell 1983). Van Velsen emphasizes the strengths of the extended case perspective, arguing ‘[…] when several or most of the actors in the author’s case material appear again and again in different situations, the inclusion of such data should reduce the chance of cases becoming merely apt illustrations’ (Van Velsen 1979: 140). Likewise, I used the extended case method to investigate how episodes revealed the actual formation of practices that were linked to other situations over time. The empirical descriptions of practices and categorizations that are extended out of the local situation displayed the very formation of a new regime of management taking place in a society at large and fueled by a complex range of processes at different scales. In such way, the extended cases provided me with an analytical prism through which the dynamics and language of managerialism were studied as governmental techniques that were being reformulated and experimented with.

‘Patient flow’ as a formative category

‘Patient flow’ (or simply ‘flow’) usually refers to the movement of patients between locations in the health care structure in general, and not exclusively to the psychiatric services. When psychiatric clinical workers at the hospital mentioned patient flow, they were referring to the system of transferring (or allocating) patients between departments in the psychiatric system. Transfers were made both in order to find the right treatment in the emergency department or in the short-term/long-term departments, and to make room for the next patient in line for specialized psychiatric treatment. This effort to rationalise clinical practices is a major part of the application of Lean principles in healthcare. Lean techniques first appeared in UK health services in 2001 and, in the USA in 2002 (Radnor, Holweg and Waring 2012).

In the American health care services the patient flow technology has been an important effort in making health care provision more efficient (Côté 2000). The category patient flow can be traced back to ‘clinical pathways’, a term which the American nurse Karen Zander at the New England Medical Center (NEMC) in Boston introduced into acute care in 1985. Zander and her colleagues at NEMC were inspired by ideas of industrial work planning from the 1950s (Scheuer 2003: 63; Vanhaecht et al. 2010). Clinical pathways are also known as ‘care pathways’, ‘integrated care pathways’ or ‘critical pathways’. They refer to a set of methods and tools used worldwide to restructure or redesign care processes (Vanhaecht et al. 2010). ‘Fast track systems’ and ‘triage’ are other terms used to describe the systematic processes of transferring patients in somatic health services, primarily in the US. The word ‘triage’ literally means ‘assessment according to quality’ and has recently been adopted to describe the process of determining the urgency of patients’ injuries (Oxford English Dictionary online). ‘Triage’ refers to a prioritizing of patients based on the severity of condition, in order to treat as many as possible when resources are insufficient for all to be treated immediately. ‘Triage’ originated during World War I when French doctors used it while treating the battlefield wounded at the aid stations behind the front. It is a system of clinical risk management employed in emergency departments worldwide to manage patient flow safely when clinical need exceeds capacity. The Manchester Triage System (MTS) is the most widely used patient flow system in the UK, Europe and Australia, employed in the treatment of emergency patients (see Mackway-Jones et al. 2006). In Norway, ‘triage’ has been employed as an administrative tool for transferring patients between hospital wards or departments in two hospitals. While clinical pathways and the like have been utilised for several years in the US, UK, and to some extent in other European countries, Norway has been a relative latecomer in introducing clinical pathways (Ramsdal and Fineide 2010).

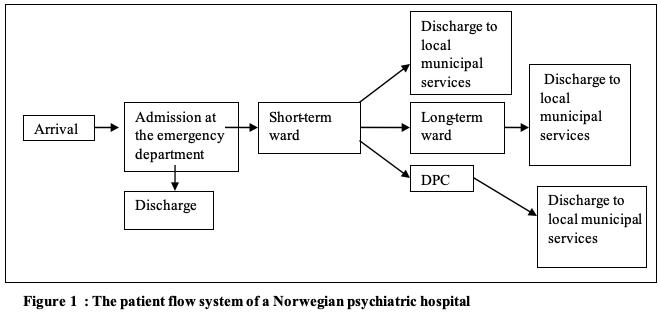

Côté outlines four common characteristics of patient flow, namely; (1) an entrance, (2) an exit, (3) a path connecting the entrance and the exit, and (4) the random nature of the health care services. Between (1) and (4) the patient meets a variety of health care resources such as hospital beds, medical procedures and different groups of health care workers and therapists. Côté’s description of patient flow as a network parallels the patient flow system of our hospital, as pictured in a flow diagram in figure 1:

Scheuer (2003) has analysed the category ‘patient flow’ in the Danish hospital context. He builds on the analysis provided by Czarniawska and Jorges (1996) in order to explore the process of institutional translation of ‘clinical pathways’. According to Czarniawska and Jorges (1996), ideas or concepts are translated to objects, then to actions that are institutionalised and repeated over time. Scheuer finds that different local translations of the category produce distinct practices and argues that the translation of such categories depends on contextual factors, ‘bricolage’ and the presence and relative power of non-human actors (or ‘actants’ in Latourian term) (Scheuer 2003: 186). He further demonstrates that ‘patient flow’ and ‘clinical pathways’ are relatively easier to use within somatic medicine (for example orthopaedic surgery) than within psychiatry, because psychiatric technology is less specific and more difficult to standardise, and the complexity of the psychiatric treatment calls for interdisciplinary knowledge. The translation process within psychiatric systems becomes more time-consuming and conflict-driven. The aim of this article is not to discuss how global concepts travel, but to expose how global concepts may be used as important technologies of improving efficiency and quality in the Norwegian health care services. The ‘patient flow’ system has clear similarities with Lean systems, clinical pathways and triage systems. The intention is to maintain productivity; resource utilisation and quality within health care services (cf. Radnor and Osborne 2013). This article discusses how this system of patient administration have contributed to reorganize Norwegian healthcare using a certain category that facilitates a rationalizing and streamlining of clinical practices.

Patient flow permeates the hospital

The main managerial purpose of the reorganization of the hospital was to improve current organizational practices, in particular the administration of patients, the so-called patient flow. The goal was to offer adequate psychiatric services to all patients in the region in need of psychiatric help. To improve the provision of services the psychiatric units were centralized into one emergency department in order to increase the capacity of admitting patients. Emergency admissions rather than elective (planned) admissions were put in the fore. Simultaneously, unitary management was introduced as a consequence of a new law on management structures in which the traditional dual management system was transformed to a unitary management structure with one manager in charge of running the unit, department or ward. The senior managers were increasingly held accountable for the hospital services and they faced a stronger pressure to keep budgets.

Flow was conditioned by the deficiency of overload. According to the Health Supervisor Authority, irresponsible overload appears when the average of capacity exceeds 95 per cent or more annually and/or that the capacity is exceeded by the use of extra beds over a given period. The hospital had often handled this situation by placing patients in corridors (“corridor beds”), but national authorities, the Regional board and the senior management increasingly defined overload as a structural problem for the quality of the health services of the hospital. The handling of overload was regularly supervised by the Health Inspector Authorities, and the management started to reorient its emphasis on the corridor patient question which made the working day much more complicated for the clinical workers. Many clinicians expressed feelings of distress and blamed it on the emphasis on flow and overload. The senior management was frequently blamed for not resisting this emphasis, and thus for being responsible for producing and escalating the pressure.

From the very outset of the research, I was struck by how the used vocabulary for moving patients within the hospital was imbued with the category ‘flow’(‘patient flow’) and of related terms such as “plugs”, “streams”, “floods”, or “waterfalls”. I increasingly understood that this had become the common and de facto way of describing the transferring of psychiatric patients within the hospital system. “Circulation”, “tidy up”, “clear” and “sort things out” were also employed, and all pointed to complex procedures of administrating patients. Although some health workers occasionally expressed strong discomfort about the terms, they were constantly used in the everyday life of the hospital.

The daily morning meeting to allocate patients and the on-going administrative efforts to eradicate corridor beds were the most central contexts where the patient flow category and related terms were used. When patients arrived at the emergency department, approximately half of the patients were considered well enough to be returned to their homes or their general practitioner after an examination and a short stay, whereas the other half was admitted, submitted to longer medical treatment, assigned to other units, and thus presumed to ‘flow’ within the psychiatric hospital system. After a short stay at the emergency department (a maximum 7 days) where the patient was diagnosed and given initial treatment, the patient was transferred to a short-term treatment unit with stays of ideally 4-5 months. After this period, the patient was transferred to long-term units at the hospital, to local district centers, or to municipal recovery services outside the hospital if he was not considered ready to be discharged. This system of ‘flow’ presupposed cooperation between the different organizational units and was based upon clinical judgements and diagnoses of each patient’s medical condition.

Patient flow was recurrently the key issue at different meetings and seminars, and the management initiated several internal projects focusing on flow. The intention of the project named Patient Flow and Dimension and the connected workshop was to identify ‘blockages’ or ‘bottlenecks’ in the current system of patient flow. The senior manager opened the workshop session by proclaiming: ‘Flow is important for the patients, but also for all of us’, referring to a common responsibility of all clinical workers for handling the patient flow. Flow was presented as the main focus for providing quality, and the participants were asked to contribute in solving ‘the challenge that patient flow represents’. Throughout the workshop, the participants identified ‘bottlenecks’ mainly as the shortage of beds in the different hospital units. Nevertheless, at the end of the workshop the senior manager put the responsibility for producing an efficient flow onto the health workers by concluding that the key to achieving an efficient flow lay in each health worker’s capability to find the right place for each patient in the psychiatric system according to diagnosis. As such, he demonstrated that the procedural logic of flow was the hospital’s most pivotal concern. This statement was accompanied by a managerial vocabulary that stressed organizational efficiency and productivity of which the health workers were held responsible.

Organizational arrangements that could benefit flow were often debated and their improvement sought, as in one of the regular senior meetings where the status of patient flow from the emergency department was the main topic. Of central interest, was the question of when a patient should be regarded as ready for transfer to services outside the hospital: Who should have the responsibility and how could they be reassured that the quality of the external services was satisfying? One of the senior managers reminded the group that these were the most critical tasks to solve. “Patient flow is a constant process and a management task”, he underlined. The director then stated; “the routines for patient flow have to become less democratic. If not, we gain nothing. This is about management decisions”. His statement triggered no discussion, and the director shortly thereafter closed this flow discussion by requiring fortnightly reports about the actual flow situation. Elaborating this last point about adequate transfers and appropriate treatment, it is certainly medical rather than organizational considerations that were in the fore. However, by closing off further discussions about how to deal with patient flow and how to define adequate discharges and transfers, the director simply ordered the senior managers to comply with the steering expectations. His concluding remark reformulated these medical concerns into primary managerial concerns, and consequently medical concerns became appropriated as a subset to flow and managerial matters. Over the course of my observations, the increasingly vocalized demand from the director and the Board for regular reports submitted the senior managers more strongly to organizational and hierarchical control. This process of refiguring clinical concerns into management issues has also been described from UK hospitals, Dent notes: ‘[c]onflicts between the clinical concerns and professional interests of the doctors are now refigured into “management issues” ’ (Dent 2003a: 111).

The handling of patient flow was obviously perceived as deeply problematic and challenging for the ones involved. None of the participants in the meeting found adequate solutions for how to achieve flow at the hospital, but flow was justified as being part of the organizational processes of improving the services for the patients. Flow was seen as the major managerial steps to improve ‘the quality of the psychiatric services’ and was thus not only presented as measuring the quality, but also constituting it and as such entered into all kinds of discussions of the hospital.

“Treatment becomes business-like”

Senior managers often referred to standstill or non-flow as the diametrical opposite of productivity. They seemed to perceive clinical productivity to be zero or low if patients were not moved within or out of the wards. Clinicians described that they often felt they had to discharge patients earlier than they preferred and medical considerations indicated. National authorities demanded an improvement of patient flow because the use of corridor beds exceeded their regulations. The means to improve the flow was to impose deadlines for discharging medical summaries and to refuse the use of corridor beds. These demands referred to the main quality indicators for the psychiatric health sector and were meant to increase and ensure adequate patient treatment. Several clinicians vented their frustration about these quality indicators for ensuring efficiency, and many expressed feelings of not having enough time to do their clinical work properly. In an interview, Jon, a psychiatrist who worked with short-term patients, underlined that the condition for working soundly with patients was to have enough time with them; “if not, we will drown in the flow of patients”, he said, pointing to the fact that not adequately treated patients would return in a worse condition than originally. ”The emphasis upon quicker discharge of patients resembles an assembly line more than a hospital with people inside. We are not doing business; we do treatment”, Jon claimed, and as many other clinical workers interviewed, he vocalised the problem of emphasising efficiency and ‘production of certain results’ in the psychiatric sector.

In several analyses from different countries, it has been described how managerial tasks are perceived by clinicians as morally subordinated to the ethical and societal ‘real’ work of the hospital: the medical treatment (see in particular Brown and Crawford 2003). When health workers (mainly the psychiatrists) at this hospital strongly emphasised the caring tasks, they were underlining a distance from the management and managerial tasks. Kirkpatrick et al. (2011) analyse conflicts between management and clinicians as processes where professionals position themselves against managerial tasks, as part of a professional struggle or reactivation of a professional hierarchy. In this material, however, to position themselves completely in opposition to managerial concerns was hard to accomplish for the professionals in everyday work. When talking about their clinical work, the professionals sometimes spoke in a way that indicated that they were rather autonomous from management, but in reality, they had to fulfil various administrative tasks such as documenting clinical practices, avoiding corridor beds, and negotiating patient transfers to produce flow. Flow, productivity, ‘deliveries’ and results structured professional work as indicated by Jon’s statement above. The observed enrolment of professionals into management is similar to what has been referred to as managerialization of professionals (Fournier 1999). If we on the other hand stick to the more established position that there is a deep split between clinical and managerial concerns, we may overlook the extent to which the category of flow in this hospital has become a managerial technology that permeates everyday working practices of the clinicians.

Resistance of the flow category?

It seemed like the aquatic terms ‘river’, ‘flow’, ‘lock’, ‘waterfall’, ‘current’, and ‘plugs/blockages’ were employed routinely at all levels of the hospital. Many health workers claimed that this was a vocabulary they had just recently started to use as they previously simply spoke of ”the number of beds” and “in which bed they could place the patient”. Gradually, flow had replaced bed as the term for describing their ordinary activities in the psychiatric hospital. In an interview with Siv (psychiatrist and senior manager), she described how she always had counted the beds at her ward in order to “have a certain control”. During our conversation about the patient situation at the ward, and about flow, she suddenly realised that she repeatedly used the term flow and found this stunning. She had never reflected on her use of this specific term before, she said. This sudden exposure of an unarticulated practice was a clear illustration of how clinicians and managers had naturalised the term through practice without questioning their use of it or of the phenomenon itself.

Nevertheless, resistance to flow as both a vocabulary and production logic occasionally surfaced, mainly at meetings where clinicians were present. Some spoke ironically of ‘lifeboats’, ‘life jackets’, or ‘drowning’ when referring to the administration of patients. At a monthly leader meeting at a long-term department, the discussion went as follows:

Berit [the senior manager] opened the meeting by presenting the recent number of corridor patients in their unit. This number showed the best result in handling corridor patients for a long time, maybe for many years, and she was very pleased. Immediately after, several critical comments were made, stating that the result pointed to greater pressures from above, rather than better conditions for treatment. “They have pleaded for life jackets [referring to clinical workers at another department], patients are drowning, and we are drowning as well, we can’t handle more”, Linda [psychiatrist] said. Katrine [psychologist] commented: “Let us rather talk about lifeboats!” (leader meeting, long-term department)

As we can see, the production results for the department were met by ironic comments. The requirement of producing efficient patient flow was described as an inundation they could not avoid. This kind of subversive critique was sometimes voiced, also when comparing their work situation with the repetitive and incessant character of industry or manuals, as one of the psychiatrists said: “Patient flow is an anti-therapeutic concept; it is as though we were a post-office or a service station for cars. All we talk about is patient flow; it is horrible, and it is professionally heart-breaking. Nowadays we only use our time on organisational stuff and on the patient flow”. The ironic portrayal of the hospital as a post-office underscores the perceived devaluation of medical work and thereby of the patient-oriented gaze. Health workers repeatedly described psychiatric treatment as being under attack from an economic logic external to medical judgment. Critical views and ironic comments that confronted the new language (production, result, flow) based upon misplaced economic rationalism were sometimes presented at staff or leader meetings but were seldom brought to senior management meetings. Neither were they mentioned in departmental reports or other management reports. Very few direct confrontations about the flow issue occurred between the management and the clinicians, and few direct actions aimed to oppose the system were described or observed. Only once one of the psychiatrists told how he had succeeded in making the management remove the words ‘deliveries’, ‘results’ and ‘production’ from a report describing clinical work. ‘Deliveries’ was removed once or twice in such reports, but shortly after the concept was reintroduced. The change was only temporary and had not any effect on further clinical practices or the language that was used in daily work. It seemed that although the clinician was deeply critical of certain dominant administrative practices and words, he had to work with them, since he did not see any realistic way to resist them. The professionals had to adjust to the system and to what was embodied in it. Kunda (1991, cited in Brown and Crawford 2003) argues that employees who have a cynical stance towards management ideologies are more easily governable. Kunda states that professionals’ playful ironic statements may undermine their capability to refuse to play out the professional practice in which they are embedded. Ironic statements thus risk becoming only carnivalesque rituals of apparent subversion. In their practical working situation, the professionals of our hospital were fulfilling requests from the management; subversive actions that actually changed organisational practices were not common.

The other minor oppositional act we were made aware of was a practice (yet not known to the management) that directly opposed the managerial discourse of flow. One of the clinicians we had met several times told how she repeatedly and strategically granted leaves to patients who had recovered, rather than merely discharging them to day treatment. If the patient was on leave, the bed would be considered occupied, and the head of the ward could then argue that their ward could not possibly receive any patients from other departments of the hospital. She described a ward that constantly had to provide vacant beds, but through this practice, she managed to avoid some of the pressure for speeding up circulation.

The strategic use of leaves as a technique for managing the ward enabled the clinical workers to challenge the managerial decision-making and to reframe the problems in a way that circumvented the flow. The fact that clinicians sometimes subvert management techniques is also described by Waring and Currie (2009). They observed how British hospital doctors resisted new procedures by undermining or circumventing the expected reporting, hence resisting managerial control over their medical work. When the clinician above manipulated the leaves, she likewise tried to avoid managerial involvement. It may be difficult to discover such resistance, and I did not observe or hear about similar incidences. As described above, a certain level of resistance did exist in the form of ironic comments and the manipulation of leaves, but these critiques of the system were not organised, and they did not really suggest alternatives to the current system and terminologies. It was thus difficult to see that resistance, irony or manipulation of the category of flow had any structural effect.

Overload and the problem of non-flow

As mentioned above, overload was stated to be a problem for the quality of the health services of the hospital1, and for this reason, both the central supervisory authorities and the local management strongly emphasised the corridor patient question. It had for a long time been a national health policy aim to make more efficient use of hospital beds (White Paper 1997: 2). With the reform of ownership structure of Norwegian hospitals from 2001, the responsibility for achieving this efficiency objective was transferred to regional health authorities, and below them local health enterprises and their managers. These managers had to develop techniques for handling the constant flow of patients in and out of the institution. The primary task became the ‘management of movement’ (cf. Rhodes 1991: 32) in the sense of not treating a relatively stable group of patients within a closed institution, but to engage in the daily administration of patients in a far more open institution. The removing of corridor beds by ‘adequate’ means could imply discharging patients earlier from the hospital, transferring them to other departments or clinics, to grant more leaves, etc. Traditionally, at this hospital overload was most likely ‘just a figure on a paper’, as Jon (clinician) stated in an interview. Actual corridor patients could be a problem for the specific ward and the patient herself, but normally the wards solved the overload by internal ward logistics such as granting leaves or redefining the treatment from twenty-four hour stay to day treatment. These were pragmatic logistic practices based on medical considerations.

The overload problem seemed to escalate within this enhanced focus on flow as the board ordered the senior management to remove immediately all corridor beds. The situation became even more critical when the Board of health supervision issued several official warnings about the corridor bed situation within a short period of time. The Board of health supervision was entitled to issue administrative sanctions against public hospitals, as either instructions or fines. The hospital attempted to handle these warnings, but did not succeed, and the Board finally imposed a day-fine that represented a substantial economic burden for several months. Throughout the following year, the hospital instigated various activities dedicated to comply with the claims, and both internal organisational steps and inter-institutional cooperative work were promoted. After several months, the fine was cancelled, but shortly after the situation worsened and corridor beds reappeared the following year. The difficult situation of constant overload was explained by the huge increase in admissions that exceeded the bed capacity of the psychiatric hospital and was seen as a problem that extended beyond the local hospital context.

A governmental strategy plan to restructure the psychiatric field aimed at increasing the capacity of the local district psychiatric centres and reducing the services of the psychiatric hospital. However, the general capacity of the DPC’s in all the health regions did not increase to the extent they were expected to. As the number of admissions to the hospital increased, the problem with the lack of capacity at the receiving end was therefore becoming more and more apparent. The correspondence between the local board of the hospital and the Board of Health Supervision continued for years, several letters and warnings were sent, and inspections were done. Corridor patients and accumulation of patients in the hospital kept producing overload of patients and hindered an efficient patient flow. Corridor patients and accumulation were in turn caused by overload and lack of flow. This apparent tautology of flow seemed to work as the causal explanation of the organizational challenges the hospital was encountering.

Reorganization through new categories

Another attempt of improving the flow situation at the hospital was to implement a restructuring plan that included the closing of a long-term ward. Two wards merged which implied a relocation of clinicians from the closed ward. In numerous staff and leader meetings, clinicians stated their uneasiness with the decision and expressed deep concerns about the consequences for the patients, and about the risk of losing their jobs. A major preoccupation was that the management renamed the wards “long-term” to “rehabilitation”. Clinicians feared that the removal of “long-term” category implied that patients were no longer seen as being in need of long-term treatment. They also feared losing specific professional experiences and expertise. The DPCs did not offer closed wards or long-term treatment services and for many clinicians these services were essential in order to deal with chronicle psychiatric illnesses. The reorganisation was seen as a serious threat to the current treatment system.

It was difficult for clinicians to gain support for their professional reservation to the reorganisation process from the management. In an interview, a clinician was asked whether the DPCs could take care of the long-term patients and facilitate a more efficient patient flow. She laughingly responded:

There are not any good professional discussions anymore; the only discussions we have are about patient flow. I am about to vomit! You know; I am deeply upset these days. The recent management decision to move the beds for long-term patients out of the hospital is devastating. Their only reason for doing this is the “lack of flow” as they formulate it. You know, through this manoeuvre, many of my patients who are severely ill are moved to another treatment ward, which has a more open, and free structure. These patients need structures and protection! We cannot just cut the relational bonds this way. Somebody has to speak out for the weakest (Psychiatrist, long-term unit, interview)

The muting of professional discussions illustrated by this citation was a symptom of what the clinicians perceived as an on-going transformation of the chronically ill patients into “revolving-door”-patients. ‘As “long-term” treatment was redefined as “rehabilitation” the quality of clinical services for mentally ill patients was getting worse. The organisational restructuring was in danger of creating “revolving-door” patients as too early discharges deteriorated the patient’s psychiatric health condition and resulted in readmissions of patients in a more critical condition. The production of more revolving-door patients in hospitals with a strong emphasis on flow has occurred in somatic health services, and the same might happen in psychiatric hospitals (Heggestad 2009). According to many clinicians; “revolving-door” patients most likely would be produced, and as one clinician said: “The patients are quickly discharged, but they reappear soon after, even sicker”2.

In this described organisational process, medical and professional arguments were apparently not taken into consideration, even though health workers saw it as a threat to clinical work and professional authority. Clinicians were overrun by the management and the general attitude was that they could not do anything to reverse these restructurings because “the system is like this”. The opponents of the flow system and of the reorganisation seemed to be unable to form a collective resistance strategy even though they articulated a shared viewpoint. Over the course of my observations, clinicians gave the impression that they were almost indifferent to oppose transformations they disliked or disagreed with because, as they said; “we are not heard anyway” and “all we get is this economic stuff about the flow”.

This kind of resignation and lack of resistance seems to bear a resemblance to what Hasselbladh et al. (2008) describe from Swedish hospitals. They note that professionals have appropriated general values of efficiency, improvements and accountability that have refigured professional autonomy and clinical practices. Hasselbladh et al. argue that collective resistance is not acted out because the professionals have appropriated these values, as suggested in this article as well. The closing and renaming of wards was done in line with the governmental action plan placing all long-term treatment services at the local district psychiatric centres. A few clinicians made an alliance with regional politicians in order to reverse the decision of renaming the services and closing the ward. Yet, the decision passed through governing boards by the decisive argument of making the hospital system more efficient and less oriented to long-term treatment. Long-term treatment was based on “an old-fashioned institutional system”, according to the decision. One of the mangers defended the decision in the following manner:

I partly acknowledge the idea of a factory that many of the workers here use as a critical image, but I think this negative image is about to change through the important transformations that we are doing now. As a clinical manager, I have to think about the hospital not only as a place for care and “storage”. The hospital cannot afford that. We must think about treatment and economy at the same time, we cannot use the entire public budget treating people at hospitals. The treatment services outside the hospital must improve because the demands of services in this field seems unlimited. On the other hand, the patient needs to prepare for a more independent life outside the hospital. We have to give the patients the responsibility to become more independent of hospital services and to be more self-confident. (Senior manager, psychiatrist)

This citation echoed the governmental policy of de-institutionalization3, which also was used as reason for closing the hospital ward as it particularly referred to economic arguments and the need to empower the patients. The ambition was to remove all the plugs that “blocked the flow’ and to promote a “seamless movement of patients” within psychiatric health services. For the health workers, the “rehabilitation” category and the closing of the ward became the core symbol of a new regime that emphasised managerial concerns above clinical ones. Logistic categories integral to the flow system became practically medical categories. Patient flow turned out to be not only an image of patient transfer, but also the crucial technology of production in the psychiatric hospital. Flow became both the linguistic criteria for, and the constitution of, treatment.

Discussion: Patient flow as ‘deep management’ technology

The handling of patient flow emerged as a difficult combination of managerial and professional concerns and dominated the day-to-day business of management and clinical work. Flow emerged as a critical problem of how to spend resources and personnel. Whether the practice of flow was adequate for treatment processes was not questioned but coalesced with managerial issues and was defined by the national health policy of efficiency and productivity. Iedema et al. (2004) describe how an Australian doctor-manager is able to produce a ‘heteroglossia’; the coexistence of, and conflict between, different kinds of speeches that mitigates between different, often incommensurable meanings and positions among clinical workers within the hospital. They describe a doctor-manager who is attuned to opposing discourses, but who succeeds in fusing contradictory positions without closing off any of them. In contrast to what Iedema et al. describe, this study suggests that heteroglossia is efficiently closed off by the management. The managers of our hospital did not try to buffer the tension between managerial and medical concerns by interposing a third position, as the Australian doctor-manager did, but rather displaced medical concerns with managerial and structural requirements. Consequently, flow as a seamless administrative logic and language of patient transfers became a predominantly and pervasive managerial concern. Disagreements about dominant practices or requirements were regarded as individual discontent and should accordingly be dealt with individually, which meant that health workers’ uneasiness with flow often was passed over in silence.

This closing off of disagreements can be analysed as a mechanism of ‘deep management’ where management is relocated from the structure and activity of the organisation into people’s subjective realm and renders them individually responsible, as Brown and Crawford (2003: 73) argue. Such ‘deep management’ technology inscribes problems onto the people who suffer from them and individuates the concerns within the “dissatisfying” individual, they argue. This mechanism represents a governing principle where management is ‘forced back under the skull’ (Brown and Crawford 2003: 76). The material of this article suggests that flow operates as a ‘deep management’ technology in the sense that flow embraces the discourse of efficiency and enhanced managerial responsibility of medical matters. Professionals or senior managers who eventually disagree with structural requirements still complied to and delivered the demanded results and reports. Managerial and professional tasks were made into overlapping concerns. Conflicts between managers and professionals were not overtly present. My understanding of the inherent dynamic of the flow practice to erase contradictions between medical judgments and administrative concerns can be further developed through the discourse of ‘patient-centred care’. This discourse was given attention when the senior managers put the individual patient in focus and underlined the patients’ needs and rights within the transfer process. Flow was legitimised by the patients’ needs and the right of the individual patient is put at the centre. The documents preparing the large-scale hospital reform of 2002 stated that:

‘[…] it is important that the advices and the experiences of the users are given a prominent place in the stage of planning, but also in the stage of implementing’ [of these health reforms]. (Ot.prp. 66 (2000 – 2001). The Health Enterprise Act)

The patient’s satisfaction with the health services has gained an increased significance in order to evaluate the quality of the health care system, including the psychiatric health services. Non-medical standards and regulations set from the outside are privileged over professional treatment regimes in order to safeguard equally good treatment to all patients. Bejerot and Hasselbladh (2011) have interpreted the strong emphasis on standardisation in health care as an attempt to ‘firmly guide’ professionals towards involving patients in ‘pre-specified activities and orientations’. The rhetoric of ‘patient-centred care’ may have influenced the professionals in our study to accept a more standardised practice of administrating patients. An increased emphasis on the patient’s rights contributes to facilitate the inculcation and legitimation of flow as a beneficial organisational practice.

Conclusion

Hospitals have been viewed as ‘professional bureaucracies’ (Mintzberg 1979), where the world of management is a world of its own and separated from the world of medicine and professionalism. The role of management in such a system is mainly to acquire sufficient resources to keep the services running and provide administrative support that allow for professional autonomy in dealing with patients. However, as shown in this article, the technology of patient flow may reveal that the professional domain may not be as disconnected from the domain of management as it has been in a professional bureaucracy. The organisational technology of patient flow provides an imperative for managers and professionals to comply with the structural requirements and the dominant language set down by the owners. The case shows that the flow technology sometimes creates tensions between managers and clinicians, in particular when medical standards are perceived to be jeopardised by an obsession with obtaining results, or simply by the use of patient flow as category. Patient flow was however never openly rejected, despite tension and the spread of oppositional comments. Flow as both the dominant production system and the dominant language closed off alternative organisational practices and thus remained apparently unassailable. The opponents of the system seemed unable to articulate and coordinate a collective resistance. Although patient flow is based on the rationality of measurement and technical administration of patients, its attention was partly drawn away from direct technicalities through an organic vocabulary that vocalised movements as inevitable (‘flow’, ‘stream’, ‘floods’, ‘waterfall’, ‘circulation’). The object of psychiatric production had apparently indiscernibly changed from clinical treatment and care to processing or sifting a statistical flow, and with this change comes an organisational logic that is not easily opposed because it appears as both natural and inevitable. Flow as an administrative technique and language is justified by the need to develop a more patient-centred and efficient health care system. Seen from this perspective, flow becomes a euphemism for efficient, rational and productive patient administration.

However, the system could not work if the professionals did not take a more managerial attitude; if they did not consider it their task to comply with standards established from outside, and engage in managerial discussions about how to achieve the objectives set by the health care authorities. To refuse to implement a system of flow seemed to be very difficult as a refusal of the system would be to refuse productivity and quality. Patient flow thus became a technique of governance, or ‘deep management’ they agreed on and which effectively concealed tensions and oppositions. In other words, patient flow operated as a structuring technique, a set of operations dealing with organisational heteroglossia3, but ‘acting as a lingua franca’ (Iedema et al. 2004: 29) that largely muted critical voices. It did not provide the possibility of multidimensional resistance as Waring and Bishop (2010) describe. This article thus argues that the category patient flow can be analysed as a managerial technology that contributes to conceal rather than expose tensions between managers and professionals. Instead, this kind of technology appears as patient-oriented and quality guaranteeing and it is therefore not perceived as a technology in the service of management. In the same move, it also hides its transformative implications for medical treatment and perspective on psychiatric illness. It is difficult for professionals to refuse flow as the dominant terminology used and the organisational processes involved appear as necessary and inevitable preconditions for an adequate organisation of psychiatric health care. Based on my observations, I thus argue that the application of patient flow as a dominant category and technology enforced the managerial requirements and prevented the raising of clinical considerations within the psychiatric health services of this specific hospital.

Acknowlegements

I would like to thank Kjetil Fosshagen and Haldor Byrkjeflot for critical comments and constructive feedback.

[1] According to the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision supervising regularly the hospitals, overload appears when the average capacity exceeds 95 per cent or more annually and/or that corridor beds above ordinary capacity are used 10 per cent or more beyond 10-20 days a year.

[2] Heggestad (2009) found that patients who have been hospitalized in a Norwegian somatic hospital department with a high degree of patient flow were at great risk for prompt readmissions. Heggestad argues that the governmental demand for increased hospital productivity, along with the introduction of a system of economic incentives, has produced a tendency for shorter hospitalization stays. The number of ‘non-elective’ [not-planned admissions, merely acute] readmissions has also increased during the period from 2002 to 2006. In this period, the time for hospitalization has been reduced from 5.6 to 4.8 days, while the use of day-treatment has increased. The non-elective readmissions have increased by 28 per cent. The production of an increased revolving-door patient dynamic in the psychiatric hospital may parallel what is going on in the somatic sector.

[3] In the reform of Norwegian health care sector, local government and de-institutionalization was extensively emphasized. The Action Plan of Mental Health was introduced in 1998 and aimed at reducing the hospital services and increasing the mental health service of local mental health centers.

[4] Iedema draws the concept of ‘heteroglossia’ from Bakhtin. This concept describes the coexistence of, and conflict between, different kinds of speeches. Heteroglossia ‘[…] embodies complex interactive dynamics, at times even manifest in one and the same stream of talk’ (Iedema et al. 2004: 17; emphasis in original).

References

Bejerot, E., Hasselbladh, H. (2011) Professional autonomy and pastoral power: the transformation of quality registers in Swedish health care, Public Administration, No 89(4), pp. 1604–1621.

Brown, B., Crawford, P. (2003) The clinical governance of the soul: ‘deep management’ and the self-regulating subject in integrated community mental health teams, Social Science & Medicine, No 56, pp. 67–81.

Côté, M. J. (2000) Understanding Patient Flow, Decision Line, March 2000 (http://www.decisionsciences.org/DecisionLine/Vol31/31_2/index.htm) (accessed 16.09.11).

Czarniawska, B. Jorges, B. (1996) Travels of ideas, Czarniawska and Guje Sévon (eds.), Translating Organizational Change, Berlin/NY: Walter de Gruyer.

Dent, M. (2003) Managing Doctors and Saving a Hospital: Irony, Rhetoric and Actor-Networks, Organizations, No 10, pp. 107–127.

Evens, T. M. S., Handelman, D. (eds.) (2005) The Manchester school: practice and ethnographic praxis in anthropology, Social Analysis, No 49(3).

Evens, T.M.S., Handelman D. (eds.) (2006) The Manchester school: practice and ethnographic praxis in anthropology. New York: Berghahn Books.

Exworthy, M., Halford S. (1999) Professionals and the New Managerialism in the Public Sector. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Fitzgerald, L., Ferlie, E. (2000) Professionals: Back to the Future? Human Relations, No 53(5), pp. 713–38.

Fournier, V. (1999) The Appeal to “Professionalism” as a Disciplinary Mechanism, The Sociological Review, No 47(2), pp. 280–307.

Freidson, E. (2001) Professionalism: the third logic. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Goffman, E. (1961) Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Anchor Books.

Grey, Ch. (1997) Management as a Technical Practice: Professionalization or Responsibilization?, System Practice, No 10(6).

Harrison, St., Pollitt, Ch. (1994) Controlling health professionals: the future of work and organization in the National Health Service. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Hasselbladh, H., Bejerot, E., Gustafsson, R.Å. (eds.) (2008) Bortom New Public Management –Institutionell transformation i svensk sjukvård. Lund: Academia Adacta.

Heggestad, T. (2009) Hospital readmissions and the distribution of health care. Analyses of Norwegian national register data. PhD thesis, University of Bergen.

Iedema, R., Degeling, P., Braithwaite, J., White, L. (2004) ‘It’s an Interesting Conversation I’m Hearing’: The Doctor as Manager, Organization Studies, No 25(1), pp. 15–33.

Kapferer, B. (2005) Situations, Crisis, and the Anthropology of the Concrete: The Contribution of Max Gluckman, Social Analysis, No 49(3), pp. 85–122(38).

Kirkpatrick, I., Dent, M., Jespersen P. K. (2011) The contested terrain of hospital management: Professional projects and healthcare reforms in Denmark, Current Sociology, No 59(4), pp. 489–506.

Kitchener, M. (2000) The ‘bureaucratization’ of professional roles: the case of clinical directors in UK hospitals, Organizations, No 7(1), pp. 129–154.

Kunda, G. (1991) Ritual and the management of corporate culture: A critical perspective. Paper presented at the Eighth International Standing Conference on Organisational Symbolism, Copenhagen, June 1991.

Mackway-Jones, K., Marsden, J., Windle, J. (eds.) (2006) Emergency Triage: Manchester Triage Group. Malden: Blackwell.

McNulty, T., Ferlie, E. (2004) Reengineering Health Care. The Complexities of Organizational Transformation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mintzberg, H. (1979) The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of the research. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Mitchell, J. Cl. (1983) Case and Situational analysis, Sociological Review, No 31, pp. 187–211.

Power, M. (2007) Organized Uncertainty. Designing a world of risk management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Radnor, Z., Holweg, M., Waring, J. (2012) Lean in healthcare: The unfilled promise?, Social Science and Medicine, No 74(3), pp. 364–371.

Radnor, Z., Osborne, St. P. (2013) Lean: A failed theory for public services?, Public Management Review, No 15(2), pp. 265–287.

Ramsdal, H., Fineide, M. J. (2010) Clinical Pathways as a Regularory Tool in Mental Health Policies. A report on Regulations in Health Policies in Norway.

Rhodes, L. A. (1991) Emptying Beds. The Work of an Emergency Psychiatric Unit. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Scheuer, J. D. (2003) Pasientforløb i praksis – en analyse af en idés oversættelse i mødet med praksis. PhD thesis, Handelhøjskolen i København.

Van Velsen, J. (1979 [1967]) The extended case method’, Epstein A. L. (ed.) The craft of social anthropology, Oxford: Pergamo, 129–149.

Vanhaecht, K., Panella, M., van Zelm, R., Sermus, W. (2010) An overview on the history and concept of care pathways as complex interventions, International Journal of Care Pathways, No 14, pp. 117–123.

Waring, J. J., Currie, G. (2009) Managing Expert Knowledge: Organizational Challenges and Managerial Futures for the UK Medical Profession, Organization Studies, No 30(7), pp. 755–778.

Waring, J.J., Bishop, S. (2010) Lean healthcare: Rhetoric, ritual and resistance, Social Science and Medicine, No 71(7), pp. 1332–1340.

Other sources

Meld. St. no. 64 (1999–2006) The Action plan of mental health 1999-2006, White paper from the Ministry of Health and Care Services.

Ot.prp. 66 (2000–2001) The Health Enterprise Act, White paper from the Ministry of Health and Care services.