© 2013 O.V. Gorshunova, S.A. Peshkova

2013 – № 1 (5)

Key words: fertility, pre-Islamic beliefs and practices, Central Asian cultures, saints’ cults, nature worship, female deities, sacred feminine

Abstract: It is known that in Central Asia, women, not men are traditionally responsible for procreation. The absence of children in a family is usually associated with a woman’s inability to conceive. As a result, it is often women, not men, who seek solutions to the childlessness problem and turn to a variety of ways to augment their fertility. These patterns could be explained through a local understanding of motherhood as the meaning of womanhood, or through existing religious sensibilities supporting patriarchal social structures, which, in turn, continue to sustain existing gender ideology endowing women with responsibility for their ability to procreate (e.g., Akiner, 1997; Sultanova, 2011; Tabishalieva, 2000). But we find such explanations insufficient and offer a different approach,which contributes to the understanding of primordial reasons of this differentiation and stereotypical attitudes towards women’s fertility in Central Asia. Based on an analysis of ethnographic and archaeological materials, our investigation reveals the link between the existing views on women’s fertility and the female deity worship, going back to prehistoric times. This article is part of a joint project, based on the authors’ independent ethnographic field research in the Fergana Valley in the first decade of the 21st century.

Peshkova: In the summer of 2001, I, an anthropologist fresh from a course about ethnographic methods at a graduate school, visited a sacred place in the Fergana Valley in order to re-enact, experience, and participate in a ritual expected to augment women’s fertility. I have heard stories about a particular sacred place called Yuvosh ota-pirim in the village of Kuva where one could get a lock of hair made by braiding neonatal hair and cotton from a keeper of the place (sheikh). This amulet, which is used to enhance female fertility may be obtained in exchange for a piece of cloth, some money and / or food. I visited that place and got a lock of a child’s natal hair. It was wrapped in a white cloth, and I was told that after I would give birth to a child, this cloth should be given to a mullah, who, in turn, should recite the Qur’an over my newly born child. Till then, I was instructed to keep the amulet in a safe place. When I would get pregnant I was expected to bring a lock of my own child’s natal hair to this or some other sacred site and, at some point in the future, to bring my child to this sacred place for a blessing.

This story began as an experiment, a re-enactment of what other women do, as an exercise in participant-observation. Meanwhile at the end of December 2002 I got pregnant, and in September 2003, I gave birth to a healthy boy. A year after, I cut off a lock of his natal hair and sent it to a friend in Tashkent who, during a trip to the Fergana Valley, gave this lock of hair to a keeper at a sacred place.

Other women are not as lucky as I am. I met Sumaya at her brother’s wedding in the summer of 2001 in Fergana. She was hiding behind the piles of fabrics, clothes, and scarves, the newlyweds’ presents in a room in the part of house that will become the newlyweds’ living quarters. The groom’s mother, who invited me in to see the presents, introduced her, “My daughter, Sumaya. She is not well. She has a headache.” When the old woman left the room, I turned towards Sumaya. I wondered why she was not among the guests celebrating her brother’s wedding but hiding in this room. The reason, she said, was infertility.1

Sumaya got married a year ago, when she was twenty two years old. She and her husband did not use contraception, yet she could not get pregnant. A local gynecologist diagnosed the woman with an ‘undeveloped’ uterus. Sumaya reckoned it was a medical issue: it was not a curse or God’s punishment. But after a year of various medications, injections, hospitals, and reassurances, she still could not conceive. “The only thing I want is to have a baby”, she said. “I am afraid I will not be able to though.”

Bio-Social Reproduction

Ethnographic research shows that in Central Asia it is often women, not men, who are held responsible for children. In childless couples, it is women, not men, who are stigmatized for their inability to conceive and thus seek transcendental intersection to augment their fertility. These patterns could be explained through a local ideological understanding of motherhood as the meaning of womanhood, or through existing religious sensibilities supporting patriarchal social structures, which, in turn, continue to sustain existing gender ideology endowing women with responsibility for their fertility (e.g., Akiner, 1997; Sultanova, 2011; Tabishalieva, 2000). We find both such explanations of gendered social responsibilities in Central Asia insufficient. If biology determines individual capacity for procreation, historical continuity of ideological connection of female qualities with life-giving and preservation of offspring both encourages and enables women to augment their reproductive capacities. We agree with Linda Alcoff, who argues that our sexed identities, the way we embody our biological capacities, vary, but for women, the knowledge about the physiological possibility of bearing and having a child creates a set of experiences that must be dealt in a different, ‘at least not in the same’, way from those ‘who grow up male’ (Alcoff, 2006, p. 176). Women’s procreative responsibilities in the areas where we conducted our research are but one example of dealing with this knowledge and overcoming biological capacities by any means necessary.

As it is known, social life of the Central Asian population is gendered. There both traditional institutions and national ideologies emphasize women’s role as a foundation of society (cf. Ahmed, 1992; Najmabadi, 1998; Tohidi, 1999). In light of this women are expected to act as the caretakers and teachers of future generations and therefore, creators of the future moral/national/local community. But more importantly they are biological beings who have a capacity to bear children. From this perspective, female fertility becomes especially poignant; it not only connects daily life and social benefits, but also links female procreative abilities to social reproduction at large (cf. Inhorn, 2006).

‘Home with children is a bazar (market) but without children it is a mazar (graveyard)’, an Uzbek proverb says. This allegory is quite accurately reflects the stereotypical attitude towards posterity among indigenous peoples of the region, where the importance of having children is caused not only by individual desire for procreation and companionship but also by ideals about life-cycle, which is first of all oriented to marriage and multiple children. Having children determines social status of a family, therefore, in most cases, childless unions do not last. Sometimes to avoid such a problem a couple unable to have biological children adopts their relatives’ child. In the case of a wife’s infertility, a husband can also marry again. In a polygynous marriage, the childless wife would become a social mother of the offspring. Divorced women, left by their husbands due to her infertility, could marry divorced or widowed men with already existing children (Gorshunova, 2006, pp. 149-50).

Biological capacity for reproduction is critical in formation of individual identity, as humans live in biologically sexed bodies. As Linda Alcoff write, ‘we should underrate the role of biology in individual experiences of their sexed identities’; having knowledge ‘that one may become pregnant and give birth to children in the future affects how one feels and thinks’ and ‘provide the constraints on undecidability and total fluidity for the development of female and male sexed identities’ (Alcoff, 2006, p. 176). Although childless marriage is distressing for both spouses, its consequences affect women more than they do men (Gorshunova, 2006, p. 150). Motherhood is considered to be central and the most important role played by a woman during her life-cycle. From early childhood girls are taught necessary skills associated with taking care of their offspring. Thus, their social horizons closely reflect their biological capacity to bear children.

The knowledge about women’s ability to bear children informs not only their psychological health but also their social status. Individual inability to procreate results in social stigma; childless women are often avoided because they are thought to be able to ‘infect’ other women with infertility through physical contact or the emotional jealousy they are said to feel towards fertile women. Even though some studies show that fifty percent of cases of couples’ infertility are caused by men’s inability to conceive, similar to other socio-historical contexts, in Central Asia, women are often held responsible for the couple’s inability to conceive (Inhorn, 2006, p. 218). Therefore, mainly women seek transcendental intersection to augment their fertility.

Although biological reproductive capacity sets parameters for social reproduction, women and men’s desire of offspring leads them contest these parameters. They seek medical treatment, and use other means, such as IVF, which is utilized, in our experience, only by elites. Every woman of childbearing age in the valley is supposed to have access to ‘women’s consultations’ (zhenskie konsultatsii) that are medical clinics that monitor and advise on reproductive practices. In order to overcome infertility, aside from the above, childless women visit sacred sites. The folk healers and religious practitioners offer treatments of infertility as well.

Remedial Procedures and Ritual Practice

Inasmuch as infertility can be a tragic experience, sometimes it is taken to be a sign of a special mission; a sign of God’s will for an individual to devote her or his life to spiritual leadership or healing (Gorshunova, 2006, p. 151). But this understanding of reason of infertility is rare and mainly extended to a group of individuals (sayyid) who claim to descend from the Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima. Sometimes infertility is interpreted as God’s punishment. In most cases, however, other explanations prevail including ‘sleeping fetus’, ‘catching a cold’, and being possessed by spirits.

Healing. The different categories of male healers (talyb and duakhan), and especially female healing practitioners referred to as momokamper or karakamper (elderly women who practice ‘magic’) are said to possess special knowledge and powers.

In cases when female infertility is explained as the result of ‘cold’ (sovuklyk) women are given a ‘hot’ treatments (issiklyk), such as the warm sand baths, and ‘hot’ diets, added to a vaginal massage and other procedures aimed to recover the balance of cold and hot in a woman’s body. These procedures are accompanied by prayers and ritual slaying of a chicken or other domestic animal.

Some females unable to conceive are said by local healers to have a ‘sleeping uterus’, which must be ‘awakened’; other women are believed to be really fertile but the fetus is stuck to the walls of the stomach and needs to be unstuck (see also Gorshunova, 2006, p. 151). ‘The shaking the stomach’ is a method that is thought to cure infertility, to wake up the fetus, or to prevent a possible miscarriage. During this procedure a female healer palpates and then shakes the patient’s stomach. In addition a healer might prepare a black chicken’s egg, which is warmed up and cracked. The yolk of the egg is inserted into a female’s vagina that is said to ‘sack in the yolk’ and is thought to awaken the uterus and enhance female’s fertility (Peshkova, 2005).

One of the causes of infertility that are mentioned by healers is a woman’s possession by spirits such as Sarykiz and jinn, among others. To augment the woman’s fertility the spirits needs to be exorcised and, if the procedure does not work, the woman has to ‘accept’ the spirits to control them, that means she must become a bakhshi [shaman] (Gorshunova, 2006, p. 151).

Pilgrimage to sacred places (ziyarat). The most popular form of infertility treatment is to perform a series of rituals accompanying prayers to a local saint at his or her worship place. The Arabic term mazar (‘place of visit’) is commonly used to refer to a holy place in the Fergana Valley and in other parts of the region. At a sacred site, women-pilgrims come early in the morning and stay at the place for several hours though some stay overnight. They bring to the place a domestic animal for sacrifice, and baked goods that are left at the site. A piece of cloth (often white in color and about three meters long) and some money are given to the keeper of the place (sheikh). The meat of the slaughtered animal are used to cook a ritual dish, such as osh (rice and lamb) or domlama (vegetables and meat). Before the food is cooked and consumed, women clean around the saint’s grave. They sprinkle water and sweep the ground that demonstrate women’s recognition of the saint’s power and are meant to purify both holy ground and women’s bodies ridding them from malicious spirits and averting an ‘evil eye’ often believed to affect women’s ability to conceive. The prayers are followed by women’s requests for pregnancy that are, in turn, followed by promises to thank a saint and to sacrifice another animal if the request will be heard and answered.

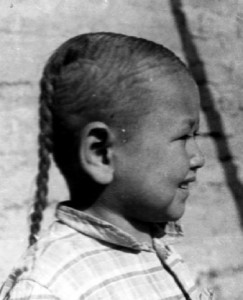

Purchasing a lock of hair made ritually by braiding neonatal hair (kokyl) at sacred sites is one of the practices said to remedy female infertility or prevent a miscarriage. This practice includes a longitudinal set of rituals that start with the hair’s purchase. Kokyl wrapped in a cloth is kept under the woman’s pillow for several days, and then put in a suitcase. If a female becomes pregnant some time after the ritual, she has to demonstrate her gratitude to the saint by visiting the place again and by an animal sacrifice. Her child’s natal hair is a sign of devotion of the child to the saint. A small area on the top of the child’s head is kept unshaved until a sequential ritual of shaving the hair is performed a year or more after the child’s birth. On such occasion the woman’s family sacrifices a lamb and redistributes the meat among their neighbors, relatives, and the poor, who are expected to give thanks to God for this blessing, for the child’s birth. The elders of the family, clergy such as otin (female religious leader) or mullah are invited to commit prays and rituals. Later this day the unshaved piece of the baby’s hair is shaved off and brought back to the sacred place where another childless woman may purchase it. (Peshkova, 2005).

- Uzbek child with a ritual pigtail (kokyl) that is a sign of his dedication to a saint. Fergana, 1970. Photo Collection of the Fergana regional museum.

Sacred Imagery and Nature

There are different types of mazars in the region. Most of them can be divided into two groups. The first one includes the sites where the central shrine is a saint’s grave. These are burial places of local Sufi leaders and other authoritative religious practitioners. The other group consists of holy sites where the tomb is absent, or there is a structure resembling a vault or a mound that imitates a grave. These are so-called ‘fictitious’ graves. Mazars of this kind have a number of specific features. Their sacred objects as a rule are trees, caves, water-springs or/and other natural objects. Although they too are the places of saints the saints venerated at these sites were not real people, but mythical personages. The absence of their life stories, as well as their particular names (e.g., Lady Rebellious, Pregnant Elm, or Forty Virgin Spirits) confirms their mythical origin. Their legends often have the same plot telling a story of a righteous man or woman, the only inhabitant of a village, who survived enemies’ (kafirs’) attack. The culmination of all these stories is a miraculous disappearance of the saint under the ground or inside a natural object. The term goyib, which means ‘the one who has disappeared’, is used to refer to this category of saints. The place of his/her disappearance under the ground is usually marked by a fictitious grave. Otherwise, a natural object that is believed to be the place of disappearance marks the sacred center at these sites.

Sacred places with a natural object as a main shrine are particularly popular among women. Most of them are attended exclusively or mainly by women and are called ‘women’s mazars’. The pilgrimage to these places is believed to heal female infertility and\or invigorate bodies of children born weak or suffering from illnesses (Gorshunova, 2008). To possess the holy nature objects’ life-giving power women perform rituals and come into immediate physical contact with the objects. They touch, immerse into or ingest water from the sacred springs, roll off the sacred rocks, rub into their skin the sap of the sacred trees, and so forth. The initial semantic meanings of the rituals are mainly lost under the influence of Islam. Yet, the perception of natural objects as a source of life-giving power, as well as some elements of the rituals and myths of saints show that the basis of the mytho-ritual complexes of these places is the idea of the sacred feminine, embodied in nature.

This connection is easily found at a ‘female mazar’ known as Hurkyz (‘Heavenly Virgin’) near the Shahimardan town in the southern mountains of the Fergana Valley. The complex consists of three main natural attractions – a lake, a rock and a cave – that are believed to possess life-giving power, since they all are related to the holy patron of women and children. According to local legends, Khurkyz was a maiden who dedicated herself to God. Once, when ‘kafirs’ attacked the village and killed all its inhabitants, she took a newborn child and escaped from the village. Then she had disappeared inside a cave. The cave that is the place of her miraculous disappearance is said to be her current dwelling. A big and deep lake called Kourbankul’ (‘sacrificial lake’) at its entrance is believed to be formed by her tears. The rock known as Oltin Beshyk (‘Golden Cradle’) is a cradle of the newborn, who was saved by the virgin.

The mytho-ritual complex of another sacred site, which is located near the village of Jordan (Fergana district, Uzbekistan), also demonstrates the inextricable link between the sacred feminine, personified in the holy female images, and nature. The sacred space of the site is formed around a rock with unusual reddish surface, a cave inside it, and the Oksu river at its foot. The cave is believed to be inhabited by the forty female spirits whose collective name is Chi’ltan. Despite the fact that the path to the holy place runs through difficult areas, it is a magnet for childless pilgrims and for female religious practitioners who, from time to time, visit it to pray and perform rituals, including a collective ecstatic ritual (zikr), dedicated to the spirits, and especially to a female saint who is said to be ‘like a queen among Chil’tan’. The saint has no specific name; the women call her Pirim (‘Our Pir’) and venerate her as the patrons of women and children. The place is called Tugayotkan Ayot that literally means ‘a woman giving birth’. This suggests that the cave together with other sacred natural objects at the place, as well as other caves venerated by women initially could be perceived as a divine womb. The hypothesis of the symbolic meaning of caves as the Mother Goddess’ womb in the prehistoric cultures has been sounded in “Religious Conceptions of the Stone Age” by G. Levy (1963), and later it was supported by many other specialists in the field.

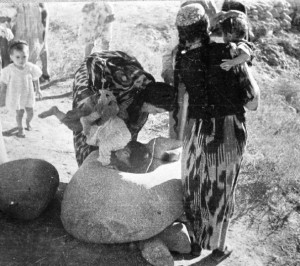

This also gives a clue to understanding the primordial semantic meaning of sacred ‘holey stones’ (teshik-tosh) that are found everywhere in Central Asia and attract special attention of women. One of these stones is found in Shakhimardan (Uzbekistan) at the place believed to be a burial of Hazrat Ali (Imam Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad). During a ritual treatment procedure, childless women either have a sit on the stone or lay down on it, in a way that the belly is positioned right over the stone’s indentation. If a ritual is aimed at augmenting health of the newborn, the head of the child is put inside this stone’s indentation.

Another holey stone with the similar function is found at the old cemetery near the Iordan village located in the surroundings of Shakhimardan. According to a legend that also connects the stone with Hazrat Ali the camel that brought the chest containing Ali’s body stumbled at this place. Trace of the camel’s knee has remained on the ground, and then it has turned to stone. At this site, rituals aimed to treat female infertility or to save sick newborns’ life are performed by an old woman who is the guardian of this sacred object.

The ritual observed by O. Gorshunova at this place was aimed to increase female fertility. It was attended by a childless woman and her female relatives who repeated pray and spells after the guardian. In addition to these, the ritual included some acts performed individually by the guardian who kneeled beside the stone picked up small pebbles and threw them one after the other in the indentation in the sacred stone.

- Sacred stone with a hole (teshik-tosh) used for ritual healing at the Yazrat Aly mazar. Shakhimardan, Fergana district, Uzbekistan. 1970. Photo Collection of the Fergana Regional Museum

The symbolism of this ritual action, which imitates seeding, points to its initial connection with the cult of fertility. According to the guardian, during the Nawrooz (New Year celebration by the ancient Iranian tradition) female religious practitioners (otins) gather around this stone for spiritual exercises (zikr). Local women also reported to hold ceremonies to venerate of Bibi Seshanbe who is a mythical personage well known to all the peoples of the region as the holy patroness of children and women. This fact in light of the studies that reveal the pre-Islamic origin of the saint leads us to suggest that this sacred place was originally a site of a female deity of fertility.

The association of natural objects with a female body or its parts that symbolize the femininity and fertility is a widespread phenomenon in Central Asia that is reflected in informal local oronyms. Examples of this include hills and semicircular rocks are called ‘a pregnant woman’. This can also be found on the plains, where most of natural shrines are trees such as elms, mulberry, and sycamore trees (Rakhimov, 2009). The holy trees’ distinctive features such as their unusual forms or huge sizes give rise to different associations in pilgrims’ imagination and define the features of ritual practices. Hollow cavities of the trees are often used as special premises for praying and conducting magic or/and healing procedures. Regardless of the shape and size of trees, pilgrims’ rituals and magic manipulations are aimed at taking possession of the miraculous power of the trees. The pilgrims contact the trees by touching and then holding palms on their face and body; they hug the trees’ trunks and get under the roots towering above the ground.

- Holy tree and its guardian at the Bibi Uvayda mazar. Fergana district, Uzbekistan, 2004. Photo by O. Gorshunova

A remarkable tree at the Khodji Baror’s sacred place in Akhunbabaev district in the Fergana region shows signs of natural objects, in which the idea of the sacred feminine and fertility is embodied. It is the biggest and oldest among holy elms at this mazar; and this is the only dry wood. The age of the elm and holes in its trunk for extracting sap give grounds to believe that tree was an object of veneration and ritual practices several centuries ago. Unlike the other trees, the elm is walled by a high fence. It is a women’s shrine that is not available to men. The elm is called Bogoz Kayragach (‘pregnant elm’) because of a large semi-spherical growth on its trunk formed by solidified sap flows. Female pilgrims hang votive objects on its dry branches and then hug the tree’s trunk, clinging to its ‘belly’. Although the women’s ritual manipulations aimed at the possession of the miraculous power that is believed to be contained in the tree, are a form of contagious magic, this shrine is perceived by them rather as a divine being, but not as a fetish. They address their prayers and requests directly to the tree, and vow to sacrifice a lamb or a chicken, if their prayers will be heard and answered (cf. Friedl, 1989; 2000). These prayers and actions are accompanied by wailing and lamentations to show sincerity of their desires and the depth of their grief.

While this elm is not personified, sacred trees at the other ‘women’s mazars’ in the Fergana Valley, such as Kyzlar Mazar (‘maidens’ mazar’), Childuhtoron (‘forty spirits’), Zurek Momo (‘mother Zurek’), as elsewhere across the region, are often associated with particular female saints. For example, forty one symbolical trees at the Childuhtoron sacred place near Kokand town in the Fergana district are identified with a group of female saints. The eponym is derived from the collective name of the forty virgin spirits – Chil’tan – that were mentioned above. Forty holy fig trees at the mazar are believed to be the living embodiments of these virgins, while the mulberry tree among them is said to be the virgins’ mistress.

- The Childuhtoron Mazar. Holy trees inside it are identified with female saints; an mound marks the place of miraculous disappearance of the saints under the ground . Fergana district, Uzbekistan, 2004. Photo by O. Gorshunova

Different saints, divine patronesses of women and children, are venerated in Central Asia. The most well-known of them are Bibi Seshanbe (‘Lady of Tuesday’) and Bibi Mushkilkusho (‘Ledy who solves difficulties’). Among the Tajiks living in the mountains the saint called Dev-e Safid (‘White Deity’) is particularly popular (Andreev, 1927). Despite the presence of some individual features, these saints’ images show a number of similarities found in their appearance and attributes described in legends and stories of the custodians of sacred sites and female practitioners, who usually performs rites and rituals honoring the saints (Gorshunova, 2012, p. 153). This suggests that the tradition of the female saints’ veneration had been formed and developed in the local cultures in the framework of a single polytheistic system. The importance of natural objects in veneration of these saints points to archaic nature of the system of beliefs and rituals, on which the holy patronesses’ cults are based. Similar beliefs and practices have been recorded by ethnographers in the mountains of the Hindu Kush, in the religions of the Nuristani peoples, formerly kafirs (‘infidel’), including a small community of the Kalash, whose polytheism through the gods’ essential identity with nature suggests a form of pantheism in which everything is considered divine, and life is not understood as something separate from nature (Ferlat 2005, p. 951).

Three main goddess of the Hindu Kush’ pantheon have features in common with the Central Asian saints, the patroness of women and children. All the three – the grain-goddess Dizane, the fecundity goddess Nirmali who protects pregnant women, and the goddess Kshumay who presides over the fertility of the goats – are believed to be the embodiment of life-giving power. Each of the three are symbolically identified or associated with natural objects. Myths depict the goddess Dizane either as a huge tree (Eyetmarr, 1986, pp. 98-104), or in form of a tree trunk, the roots of which symbolize the goddess Nirmali (Robertson, 1896, p. 386). Cowry shells symbolize the goddess Kshumay whose hat, according to a hymn in her honor, is decorated with these shells. The Kalash women and girls wear similar hats ‘on the goddess’s orders’ (Eyetmarr, 1986, p. 114, p. 396, p. 373). This practice is also widespread in Central Asia among Uzbeks, Tajiks and Turkmen who use cowry shells to decorate women’s and children’s headwear, where the shells serve as amulets and magical means for increasing the vitality and ability to bear children. The link between this custom in Central Asia and a local female saint was discovered by G. Snesariev who reports that in Khorezm, the aft part of some river vessels has the form of a woman’s head; headwear on the ‘heads’ are decorated with cowrie shells. In his opinion, these decorative elements depict the head of a local female saint called Ambar-Ona, ‘whose image genetically traced back to the image of an ancient goddess’ (Snesarev, 1969, p. 247).

Short Detour into History

There is a widespread opinion that the prototype of popular Central-Asian patronesses of women and children as well as of some female personages of the local pandemonium (such as Momo, Albasty) is Ardvi Sura Anahita, the Avestan goddess of fertility (Andreev, 1953, p. 81; Snesarev, 1969, pp. 243-247; Gundogdyev, 1998). Although the Iranian origin of well-known female saints (Bibi Seshanbi; Bibi Mushkilkusho, Ambar-Ona, and other) is not in doubt, there are a big collection of artifacts suggesting that the local saint veneration tradition of has deeper roots going back to pre-Zoroastrian times. The earliest evidence of the female deity worship in Central Asia was found at the Altyn-Depe settlement in southern Turkmenistan and dated to the fifth millennium BC, the early eneolithic period. These are small clay nude female figurines with a columnar base instead of feet. M.G. Vorobjeva, while comparing these artifacts to some images of goddesses found in the Near East, had come to the conclusion that goddesses are embodied in the Central Asian statuettes, in which the columnar base can be interpreted as a tree trunk (1968, p. 142). Iconographic features as well as incisions and pinholes in the lower parts of some figurines point to their ritual use. For instance, one of them depicts a pregnant divine with a swollen belly, covered with elaborate designs carved with a sharp toll a deep incision in the lower abdomen. This can indicate the use of the figurines in magic practices aimed at facilitating childbirth (Masson and Sarianidi, 1973, p. 11, p. 88) and/or increasing fertility.

Terracotta figurines depicting the goddesses of fertility were popular in ancient Bactria, a Bronze Age civilization of Western Central Asia, dated to ca. 2300–1700 BC, located in present day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan. Many of the highly stylized flat statuettes discovered in southern Turkmenistan by N. Masson and V. Sarianidi (1973) are decorated with symbolic patterns of tree motifs. Some figurines of this collection are decorated with are engraved with a pattern imitating a plant or a tree, which seemingly grows out of the symbolic female triangle located below the abdomen, in the lower part of the figurines. These figurines and the designs that they bear give some ground to assume that they reproduce an image of a deity, which embodies the idea of fertility, as well as to see in these artifacts a continuity of the tradition of identifying a female deity with a tree. The tree motifs are also found in engraved patterns of stone statuettes discovered at sites of ancient Bactria. These composite figures of soft green chlorite or steatite, with heads of white limestone, are assigned to the same period as the clay figurines, and some iconographic similarities suggest that these two groups of artifacts relate to the same cult.

- Bactrian Goddess. Clay; 16.5×7 cm. Early 2nd millennium BC. Southern Turkmenia, Altyn-Depe Settlement. The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Seated Goddess, Ancient Bactria, 2500-1500 B.C. Chlorite and limestone, Height: 5 1/4 in. (13.33 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Numerous clay female figurines of antiquity and the middle ages were found in other parts of the region, while excavating at Khorezm, Sogdiana, Khalchayan, Dalverzintepa, Ildgynly-Depe Zartepa, Barattepa, Balkh and many other sites (see Meshkeris, 1965; Pugachenkova and Rempel’, 1982; Solovyova, 2005). They reflect the idea of fertility through various symbolic attributes, such as a pomegranate, a cluster of grapes, a trefoil and a tree branch. This over-abundance of artifacts demonstrates that the female deity worship was extremely common in the period of antiquity and the middle ages in Central Asia. Later, the tradition of making terracotta figurines depicting the goddess of fertility has disappeared because of strengthening of Islam in the region, and probably as a result of Islamic ideological prohibition of anthropomorphic depictions thought to manifest idolatry. The echoes of this tradition, however, preserved in Central Asia in the form of ritual dolls made of different materials and designed mainly for wedding ceremonies and rituals associated with childbirth. These dolls bear in themselves the original meaning of female figurines as the symbols of fertility (see Peshereva, 1957, p. 83).

Conclusion

The Central Asian societies, as it is well known, are characterized by the gender-role differentiation, caused by the ethics of Islam as well as by social norms of customary law (adat). Though the distribution of duties and responsibilities between men and women extends to many areas of life and activities, the exclusive responsibility for the procreation imposed on women in Central Asian societies, we argue, cannot be explained only through the social and ethical norms and ethno-cultural traditions (e.g.,Tabishalieva, 2000). Analysis of empirical material leads us to conclude that attitudes towards biological reproduction as the exclusively women’s sphere that are typical for the Central Asian Muslim population is a transformed reflection of archaic religious and worldview representations about the sacred feminine. The areal of distribution of these representations in the past is not limited to Central Asia, as evidenced by ethnographic and archaeological data (e.g., Adovasio et al., 2007; Conard, 2009; Dames, 1977; Davies, 2000; Gimbutas, 1991; Mellaart, 1963).2

Iconographic features of the female figurines found in different parts of the region, indicate an ideological link between the divine feminine, fertility and nature in the representations embodied in these artifacts. Our ethnographic research shows that the archaic beliefs connected to the sacred feminine, embodied in divine female images, have not disappeared completely. While transformed under the influence of other religions, widespread in pre-Islamic Central Asia, and particularly in the result of Islamization of local cultures, they still are manifested in healing practices, in the symbolism of sacred objects at holy places, and are reflected in myths and mystic images of local pandemonium and hagiology. They can also be traced in the rituals of female pilgrims at sacred places; they are manifested in the pilgrims’ perceptions of natural objects as sources of life-giving power and in their associations of these objects with motherhood and femininity. All this points to the continuity of tradition originally focused on the goddess of fertility, which has been identified with nature in different archaic cultures, including those existed within the borders of modern Central Asia.

Notes

- The native peoples of Central Asia believe that childlessness is like infectious disease that can be transmitted from a childless woman to other women through physical or visual contact. It is also believed that brides are particularly susceptible to this “disease”, therefore childless women are usually not invited to wedding ceremonies.

- For a psychoanalytic discussion of feminine and sacred see Kristeva, 2001; Stone, 1978; Waraksa, 2009.

References

Abramson, D. and Karimov, E.E. (2007), “Sacred sites, profane ideologies: religious pilgrimage and the Uzbek state”, in Everyday Life in Central Asia: Past and Present, Sahadeo, J. and Zanca, R.G. (Ed.), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 319–338.

Adovasio, J. M., Soffer, O. and Jake Page, J. (2007), The invisible sex : uncovering the true roles of women in prehistory, Smithsonian Books: Collins, New York.

Ahmed, L. (1992), Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of A Modern Debate, Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Akimushkin, O.F. (2005), “The burial ritual “sadir” of the Tadzhik [sic] populations of Pendjikent’, in Central Asia on display: proceedings of the 7th Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies, Rasuly-Paleczek, G. and Katschnig, J. (Ed.), Lit, Münster; London, pp. 33–37.

Akiner, Sh. (1997), Between tradition and modernity : the dilemma facing contemporary Central Asian women, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York.

Alcoff, L. (2006), Visible identities : race, gender, and the self, Oxford University Press, New York.

Andreev, M.S. (1927), “Central Asian version of Cinderella”, Po Tadzhikistanu. V.1, Tashkent.

Conard, N. J. (2009), “A female figurine from the basal Aurignacian of Hohle Fels Cave in southwestern Germany”, Nature, 459(7244), pp. 248–52.

Dames, M. (1977), The Avebury cycle, Thames & Hudson, London.

Davies, P. (2000), Antique kilims of Anatolia, W.W. Norton & Co., New York.

Denber, R. and Levine, J. (2005), “Bullets Were Falling Like Rain”: the Andijan Massacre, May 13, 2005, Human Rights Watch, New York.

Eyetmarr, K. (1986), Religions of the Hindukush, Nauka, Moscow.

Friedl, E. (1989), The Women of Deh Koh: Lives in an Iranian Village, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Friedl, E. (2000), “Islam and Tribal Woman in a Village in Iran”, in Unspoken Worlds: Women’s Religious Lives, Falk, N.A. and Cross, R.M. (Ed.), Wadsworth, Thomas Learning, Belmont, CA, pp. 157–168.

Gorshunova, O.V. (2006), Uzbek Women: Social Status, Family, Religion. (On Materials Drown from the Ferghana Valley), IEA RAN, Moscow.

Gorshunova, O.V. (2008), “Sacred trees of Khodzhi Baror: phylolarty and the cult of the female deity in Central Asia”, Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie, 1, pp. 71-82.

Inhorn, M. (2006), “The worms are weak”: male infertility and patriarchal paradoxes in Egypt”, in Islamic Masculinities, Ouzgane, L. (Ed.), Zed Books, New York, pp. 217–237.

International Crisis Group (ICG) (2007), Political Murder in Central Asia: No Time to End Uzbekistan’s Isolation, International Crisis Group, Bishkek, Brussels.

Kandiyoti, D. and Azimova, N. (2004), “The communal and the sacred: women’s worlds of ritual in Uzbekistan”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 10(2), pp. 327–349.

Khalid, A. (2007), Islam after Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia, University of California Press, Berkley.

Clement, C. and Kristeva, J. (2001), The feminine and the sacred, translated by Todd, J.M., Columbia University Press, New York.

Lubin, N. and Rubin, B.R. (1999), Calming the Ferghana Valley: Development and Dialogue in the Heart of Central Asia, The Century Foundation Press, New York.

Masson, V. M. (1967), “Protogorodskaya civilization of the south of Central Asia”, Sovetskaya arkheologiya, № 4.

Masson, V. M. (1988), Altyn-Depe, University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Masson, V.M. and Sarianidi, V.I. (1973), Central Asian terracotta of the bronze epoch. Experience of classification and interpretation, Nauka, Moscow.

McGlinchey, E. (2007), Divided faith: trapped between state and Islam in Uzbekistan, in Everyday Live in Central Asia: Past and Present, Zanca, R. and Sahadeo, J. (Ed.), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 305–318.

Mertens, J., Muscarella, O., Roehrig, C., Hill, M. and Milleker, E. (1992), “Ancient art: gifts from the Norbert Schimmel collection”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 49, no. 4, available at: http://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258919.pdf.bannered.pdf.

Metcalf, B.D. (2009), “Telling the story of Islam in Asia: reflections on teleologies and timelessness”, ASIANetwork Exchange, XVI, pp. 2–23.

Najibullah, F. (2003), Central Asia: A Visit to Ferghana valley. Exploring the Roots of Religious Extremism, available at: www.enews.ferghana.ru/article.php?id=220.

Najmabadi, A. (1998), “Crafting an educated housewife in Iran”, in Remaking Women, Abu-Lughood, L. (Ed.), Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 91–126.

Omar, R. (2006), Violence and the State: A Dialogical Encounter between Activists and Scholars, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cape Town.

Peshereva. E.M. (1957), “Toys and kid games of Tadzhiks and Uzbeks”, Sbornik Museya Arheologii I Etnographii, tom 17, Leningrad, pp. 22-44.

Peshkova, S. (2005), Islamic Approach to Reproductive Health in the Fergana Valley, available at:

www.anthroglobe.info/docs/Reproductive_Health_in_Ferghana.htm.

Pisarchik, A.K. (1987), “On the remnants of the willow veneration among the Tajiks”, in Proshloe Srednej Azii (Arheologia, numizmatika I epigraphika, etnologia), Pisarchik, A.K. (Ed.), Vol., Donish, Dushanbe, pp. 251-260.

Pisarchik, A.K. (1989), “Willows in the New Year and other spring rituals among the Tajiks”, Etnographia v Tadjikistane Pisarchik, A.K. (Ed.), Donish, Dushanbe, pp. 18-37.

Rakhimov, P.P. (2009), “For what they worship the trees in Simirgandge?”, Iran-Name, 4, pp. 147-166.

Rapport, N. (2003), I am Dynamite: An Alternative Anthropology of Power, Routledge, London and New York.

Rashid, A. (1994), The Resurgence of Central Asia: Islam or Nationalism? Oxford University Press, Karachi.

Rotar, I. (2006), “Resurgence of Islamic radicalism in Tajikistan’s Ferghana Valley”, Terrorism Focus, 3(15), pp. 6–8.

Safarov, T. and Najibullah, F. (2012), Doctor Sets Out to Divorce Infertility from Tajik Cultural Taboos, available at: http://www.rferl.org/content/doctor-divorce-infertility-from-tajik-cultural-taboos/24740271.html.

Sarianidi, V. I.(1960), “Eneolithic settlement of Geoksyur (Work results of 1956-1957)”, Trudy Yushno-Turkmenistanskoi Arkheologisheskoi Komopleksnoi Ekspeditsii, T. X, Ashkhabad.

Snesarev, G.P. (1969), Relics of pre-Islamic beliefs and practices among the Uzbeks of Khorezm, Nauka, Moscow.

Solovyova, N. F. (2005), “Charlcolithic anthropomorphic figurines from Ilgynly-depe, Southern Turkmenistan: classification , analysis and catalogue”, Oxford England: BAR International Series, 1336, Archaeopress.

Stone, M. (1978), When God was a woman, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

Sultanova, R. (2011), From Shamanism to Sufism: Women, Islam and Culture in Central Asia, I.B. Tauris, London.

Tabishalieva, A. (2000), “Revival of traditions in post-Soviet Central Asia”, in Making the Transition Work for Women in Europe and Central Asia, World Bank Discussion Paper # 411, Lazreg, M. (Ed.), The World Bank, Washington D.C., pp. 51–57.

Tohidi, N. (1999), “Gendering the nation”: reconfiguring national and self-identities in Azerbaijan, in Hermeneutics and Honor, Afsaruddin, A. (Ed.), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp. 89–115.

Vorobjeva M.G., (1968), “Earliest terracottas of ancient Khorezm”, Istoria, archeologia, i etnographia Srednei Azii, Nauka, Moscow, pp. 135-146.

Waraksa, E.A. (2009), Female figurines from the Mut Precinct: context and ritual function, Academic Press, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Fribourg; Göttingen.